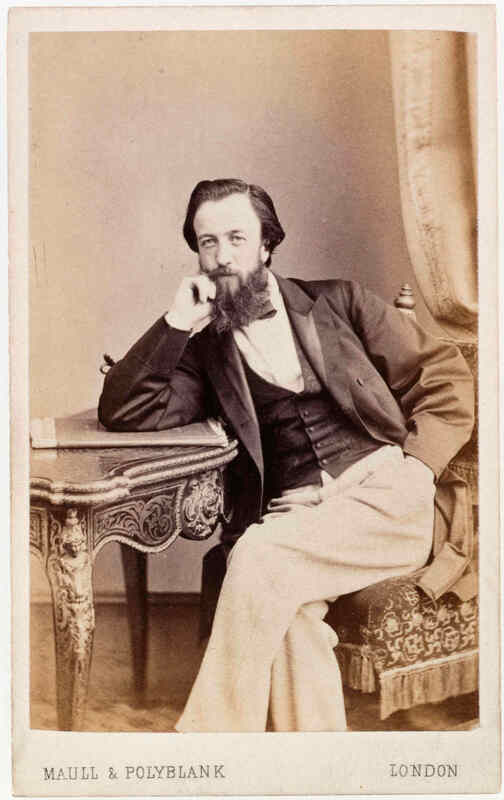

For the opening of Part III in the online program The Story of Modern Design this Friday, I selected British designer Christopher Dresser (1834-1904) as the representative of those Victorian visionaries who pioneered modern design. Dresser is an old love of mine, a true Renaissance man of the Industrial Revolution era. He perceived himself as the child of the Industrial Revolution and looked at industry as a way to progress society. Not only is he considered the father of modern industrial design, working as a commercial freelance designer for dozens factories, but his career was so multifaceted, both in practice and in theory, that he has been a world on its own. By the time Dresser died in 1904, the world was finally ready for the revolution that he had started, seeking for well-designed, factory-produced daily objects for all.

His oeuvre is widely intriguing and his involvement within the world of the Industrial Revolution included designing in glass, ceramics, furniture, wallpaper, and fiber for various companies. Yet, his most radical and iconic work is certainly a series of silver electroplate teapots, created between 1878 and 1880, a take on Japanese teapots. It was the Japanese experience which helped Dresser to revolutionize design across all mediums; thanks to this innovation, of bringing Japanese aesthetics into British design, that he made it to the list of the Pioneers of Modern Design in Nikolaus Pevsner’s landmark publication of 1936. It was at the 1862 London World’s Fair that he was exposed to Japanese art for the first time, and in 1876, he made a trip to Japan, which turned him into an expert and deepened his knowledge of Japanese lifestyle and traditions.

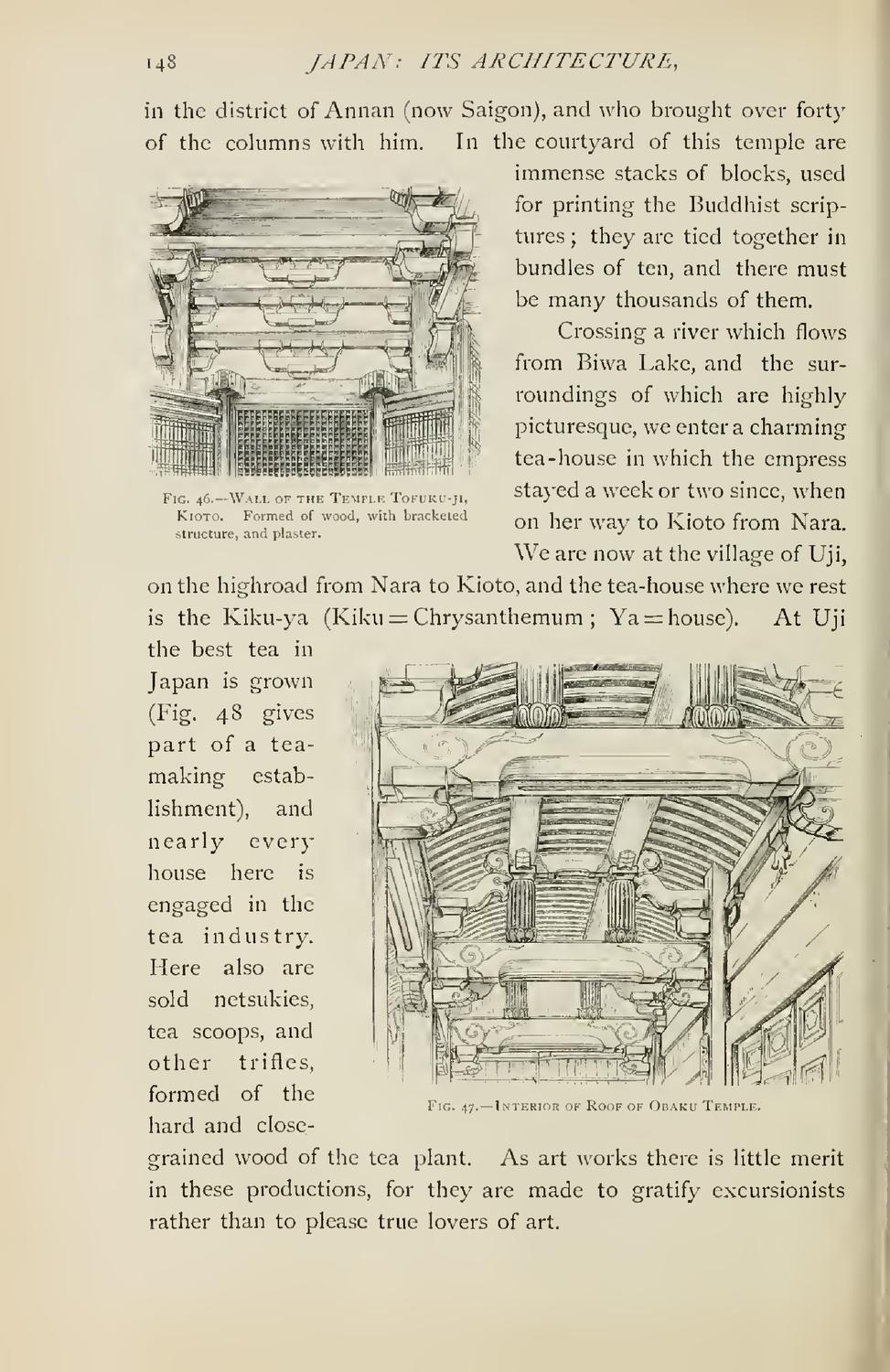

While the series of tea kettles were inspired by Japan, Dresser took his cues from a variety of international sources, India, Persia, Peru, and China, just to name four, which were often mixed together in his work. He authored four influential books on design, which provided education, career advice, and instruction. His book Japan: Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufactures of 1882. which illustrated his visit to Japan, has been credited for spreading the taste for Japonism in both Britain and the US. He had the classic training of British designers of his generation creating what was known then as ‘industrial arts.’ Graduated from the Government School of Design, which became a part of the South Kensington Museum, founded after the 1851 Great Exhibition for popularizing the taste for industrial things, Dresser was the embodiment of the way in which industry gave birth to modern design. He will be the first to open Part III of The Story of Modern Design this Friday.

His oeuvre is widely intriguing and his involvement within the world of the Industrial Revolution included designing in glass, ceramics, furniture, wallpaper, and fiber for various companies. Yet, his most radical and iconic work is certainly a series of silver electroplate teapots, created between 1878 and 1880, a take on Japanese teapots. It was the Japanese experience which helped Dresser to revolutionize design across all mediums; thanks to this innovation, of bringing Japanese aesthetics into British design, that he made it to the list of the Pioneers of Modern Design in Nikolaus Pevsner’s landmark publication of 1936. It was at the 1862 London World’s Fair that he was exposed to Japanese art for the first time, and in 1876, he made a trip to Japan, which turned him into an expert and deepened his knowledge of Japanese lifestyle and traditions.

While the series of tea kettles were inspired by Japan, Dresser took his cues from a variety of international sources, India, Persia, Peru, and China, just to name four, which were often mixed together in his work. He authored four influential books on design, which provided education, career advice, and instruction. His book Japan: Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufactures of 1882. which illustrated his visit to Japan, has been credited for spreading the taste for Japonism in both Britain and the US. He had the classic training of British designers of his generation creating what was known then as ‘industrial arts.’ Graduated from the Government School of Design, which became a part of the South Kensington Museum, founded after the 1851 Great Exhibition for popularizing the taste for industrial things, Dresser was the embodiment of the way in which industry gave birth to modern design. He will be the first to open Part III of The Story of Modern Design this Friday.

Above: Christopher Dresser, Teapot, ca. 1879, courtesy Christie’s.