When her husband, Milanese electronics magnate Giuseppe Brion (founder of Brionvega) suddenly died in 1968, his widow Onorina Tomasi Brion immediately commissioned Scarpa to design a special tomb in his birth town. For the next ten years, the Italian architect crafted the ambitious tomb, gradually adding chapels, pools, burials, merging the base and the precious, while crafting the silence out of raw concrete and glass. During all of these years, the Italian architect was secretly planning his own burial on that same site. This projects has not only become an architectural gem, but also a site of pilgrimage for anyone interested in the finest architecture culture of modern time. Like Mies’ Villa Tugendhat; like Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye; like Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasilia.

Last week, when the entire world traveled to the crowded Venice Biennale, we made our way there. Driving through the lush wine country of Northern Italy, where Prosecco was born, we spent long and breathtaking two hours of an unparalleled design experience, saved for those fortunate visitors.

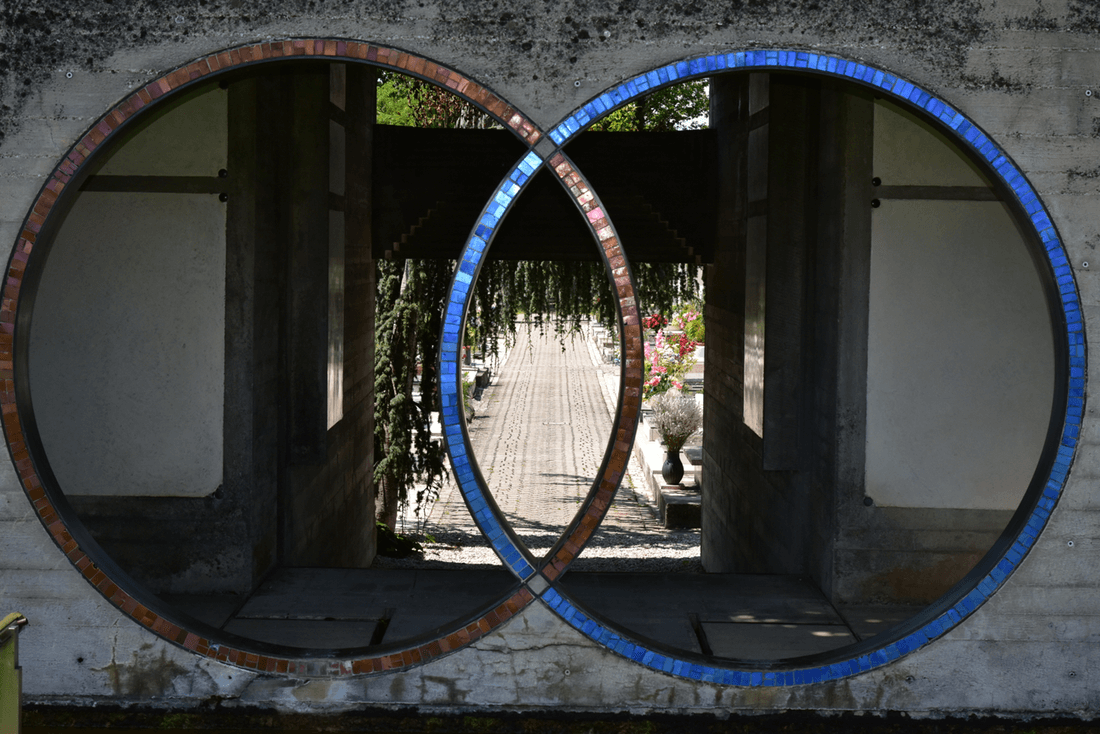

There are two principles which Scarpa mastered, the notion of looking back to the past, to the ancient, not for an iconography or language, but for the spirit, for evoking physical and emotional substance, while merging classicism with modernism. The second, is the notion of merging the base and the precious, the bare and the embellished, the mass and the details. Abstraction has long proved a way to stimulate emotions in burial and memorial architecture. Think of Mies’ Monument to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht; of

Peter Eisenman’s Memorial of the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin; of Michael Arad’s 9/11 Memorial. The Brion Tomb manifests the power of abstraction, of the dazzling bare, the unadorned mass, mixed with the remarkable geometric ornaments, and mostly the balance between the two. The tool to achieve all of these, the texture, the surface, the motifs, is a single material, concrete, and Scarpa’s commitment for detail, for craftsmanship, a skill he mastered when working as the director of the Venini Glassworks during the 30s and 40s. Decoration, he suggested, is not contradictory to modernism, but can add another layer to the pristine, to the essence of the built form.Our pilgrimage.