Everything about this spectacular villa, situated in a wealthy neighborhood, overlooking the city of Brno was mythological. It started with the young couple, Fritz and Greta Tugendhat, who commissioned the villa after seeing Mies’ German Pavilion in the 1929 World’s Fair in Barcelona. It was Greta’s father who gifted the villa to the young couple, who handed a blank check to their architect, who in turn created one of the most influential private houses of the century. The cost ended up to be equivalent to that of 150 ordinary houses, and to Mies, it was the dream patronage, which allowed him to fully substantiated his vision, employing the most luxurious materials, modern air conditioning and other systems, and an enormous glass curtain, overlooking the magnificent garden, which had remained the single ‘photograph’ of the house, keeping the unity between men and nature. It was for here, that together with his collaborator Lilly Reich, Mies designed both the Tugendhat and the Brno Chairs.

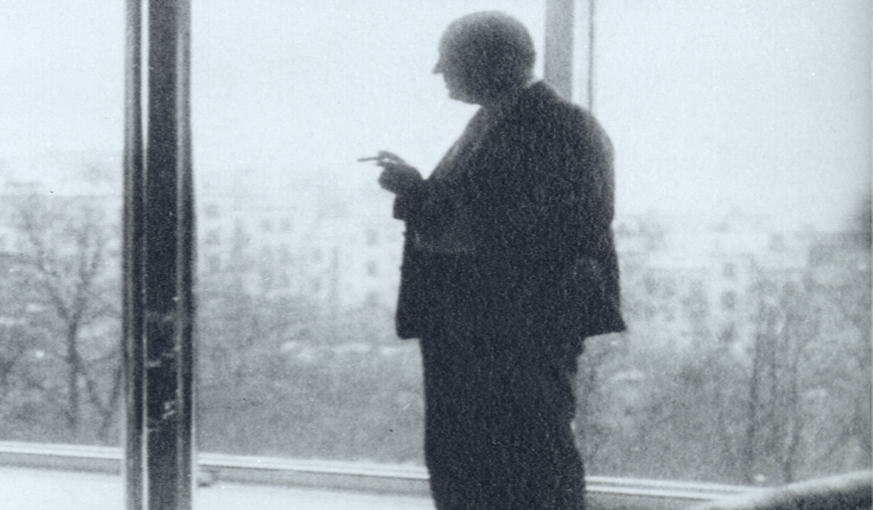

When I walked into the living room, it was when I felt the tears in my eyes, because if architecture is supposed to make you feel, then Mies has been its master. Here, within an expansive space, the definitions of the library, the sitting, room, the dining room, and the tea area, were created with the aid of walls and colums. A circular wall of Macassar ebony encloses the dining area, and one in spectacular onyx encloses the sitting area. The tragic fate of the Tugendhat was not unsimilar to many other Jewish homes. The Tugendhats enjoyed this masterpiece for just eight years before forced to leave Czechoslovakia in 1938. They ended up living in Switzerland, and nevered returned to their home. It was confiscated by the Gestapo in 1939 and was used as an apartment and office, and after WWII was served as quarters and stables for the Soviet military. It was eventually undergone major renovation that brought it to its original glory, as a monument open to the public. Most photographs are by my friend Daniel Travnicek who made this private visit possible.